My octogenarian Father was sitting in our farm market while I was waiting on customers. He wasn’t doing much; he was mostly watching the interactions and taking it all in. When things got quieter and there wasn’t anyone else in the market, he looked at me and said, “You remind me of Grandma Woody back when she had her little store.” I knew immediately what he meant, having grown up helping my Grandmother in her small neighborhood grocery.

It was interesting to hear my Father say that I resembled actions from someone on my Mother’s side of the family, the Woodards, rather than being a full-blown 100% Rouse, which is what I had heard most of my life. “You’re a Rouse, and Rouse’s do it this way!” “What are you, a quitter?’ “I have news for you. Rouse’s aren’t quitters! Never have been, and we aren’t starting now!” “Rouse’s work hard and make things happen; now get off your ass and get to work!” It seemed important to him for me to honor and behave like the Rouse men who came before me.

It was either that, or Woody just didn’t have the same forceful ring as Rouse. “Now get off your ass and be a real Woody!” Yeah, that could be it, or maybe he was mellowing in his old age.

It wasn’t that my Father had anything against the Woodard side of the family. Heck, he loved Grandma Woody. He often left his office on Main Street around noon, hung a right on Grove Street by the Post Office, drove down the hill under the train trestle, and stopped at Grandma Woody’s for lunch. He always called her “Mrs. Woody. The usual fare was a bologna sandwich on white. I’m not sure whether whole wheat bread had been reinvented at that point.

My Father now calls bologna or any deli meat’ flat meat.’ “Yeah, I always stopped in at Mrs. Woody’s for a ‘flat meat sandwich!” he said. “When did you start calling it flat meat?” I queried, “Oh, I’ve always called it flat meat!” “Ok”, I replied. “I lived with you for 16 years during your so-called flat meat era and never heard the term flat meat ever used until right now.”

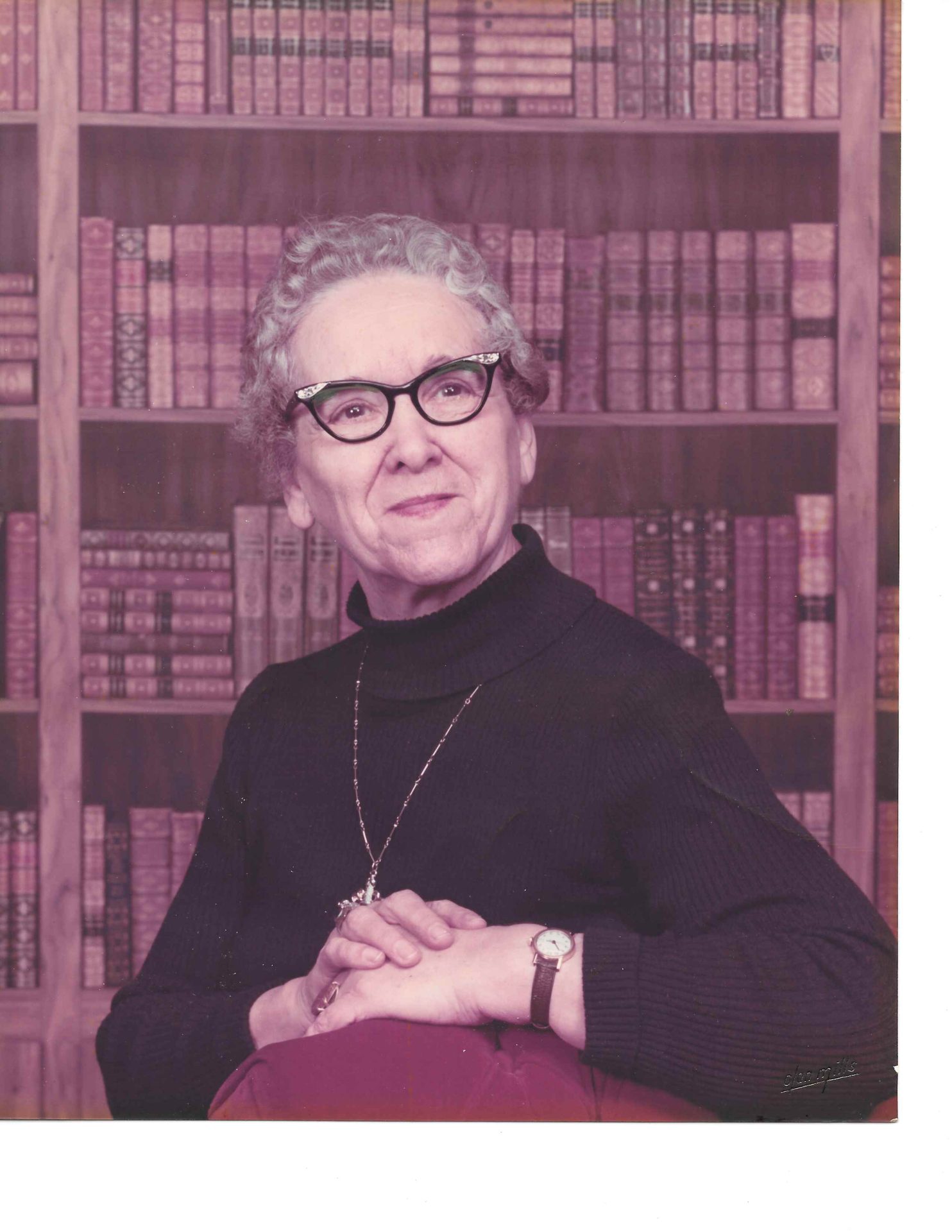

Regardless of where we both stood on the flat meat controversy, he was suddenly so enamored with his comparison between Grandma Woody and me that he even suggested we put a picture of Grandma Woody on the wall and make her the patron saint of the market!

I loved the idea, so we rummaged through some old scrapbooks, found a nice picture of Grandma, posing for the Olan Mills photographer in front of the fake bookshelf background, enlarged it, stuck it in a frame, and hung it up. Although we didn’t orchestrate the placement of her picture behind me at the market checkout counter, it appeared that she was peering over my right shoulder, proud of her grandson.

Many customers have asked about the picture since then. Who was the matronly looking woman, and why was she up on the wall? A few wanted to hear the story of Grandma Woody, and this is what I told them.

I loved my Grandma and Grandpae Woody, and what kid wouldn’t? I had a free pass to the candy shelf, the ice cream freezer, and the Coke machine in her store. Every time we had a family gathering, they would show up with a small paper bag filled with penny candy for me. My parents called the bag of offerings “The Dentist Dream Bag.” It contained items like Root Beer Barrels to initiate the tooth decay process, Smarties that led to a full cavity that required a lead filling, Bit-O-Honey to loosen my fillings, and a Sugar Daddy to dislodge them the rest of the way.

Grandma was my Mother’s Mom. She grew up on a farm, as most of our relatives from that era, the 1920s and 30s, did. She often told me the story of riding her horse to the one-room schoolhouse she attended. When she arrived at school, she dismounted, slapped the horse on the hiney, and the horse trotted back to the farm. Around the time classes ended, her Mother slapped the horse on the rear end again, and the horse headed back to school for pick up—a kind of pre-war Uber. Similar anyway, I was an Uber driver for a while, and no one ever slapped me on the ass. Most preferred using the App.

After graduating from high school, Grandma Woody worked in a small textile factory and later married Dave Woodard. Dave owned a hotel with a bar. Grandma didn’t have much luck getting her husband to leave the bar. So, in a time when divorce was nearly unheard of, especially in a little rural town, Grandma and her young daughter (my Mom) sent him packing.

It didn’t take long after that for her to meet another gentleman who, conveniently, had the same last name (Woodard) and married him. That was the Grandpa Woody I knew. His name was Orin. Grandma called him Orny. He called me Bill, which is not my name. Grandpa never called me Steve, always Bill. It was a bit weird having your Grandfather call you by someone else’s name, but even stranger, I don’t remember anyone ever questioning it. He called me Bill, and that’s the way it was, and apparently, we liked it. He worked for the Borden’s milk plant in town, driving a tanker truck from dairy farm to dairy farm to pick up milk early each morning.

On Grandma Woody’s deathbed, I approached her, nervous to ask the question I needed answered before it was too late. It seemed juvenile at a time like this, but I had to know!! I stood by her bedside, leaned over, and softly asked the question that would clear the air forever, “Grandma, why did Grandpa always call me Bill?” She took a shallow breath, looked up at me through foggy eyes. I leaned in closer as she opened her mouth to speak. This could be it —the answer I’d been waiting 18 years for. Her long-anticipated response was only three words: “I don’t know.” I said, “What?!?!” But she had drifted off and was gone. “NOOOO!!!” I bellowed in her hospital room, which woke her up.

In early 1950, Grandma decided to start her own business. She enclosed her front porch and turned it into a neighborhood store. That little store had everything: housewares, canned goods, meats, dairy products, soft drinks, and candy. Also, she got up every morning at 4 a.m. to make homemade donuts, which she sold there.

Her donuts were not the perfect donuts we know today. Each one had its own unique flair. She took a spoonful of the batter and dumped it in the bubbling grease. She was okay with whatever happened from there. Some were like a ball with no hole. Some were shaped more like a standard donut with a hole. Some were crispy. Some were soft. And we’re not talking about those donuts fried in some fancy schmancy Mediterranean oil. No, sir. Grandma fried her donuts as God intended in pig fat. That’s right, grade A, US #1 Lard!

As a little boy, I loved helping her in the store and occasionally got a fresh, warm donut. Grandma had a cabinet in her microscopic kitchen that held another one of those small paper bags. Only this one had powdered sugar in it. I delicately dropped my warm donut into the small sack. I shook the bag furiously to get complete coverage, and when the shaking was done, I pulled out a little piece of glacéd heaven!

My Grandmother’s store was located within walking distance of the town dump. It was long before any garbage regulations or “sanitary landfills.” The open-air garbage trucks picked up the garbage, hauled it to the mountain of burning trash, and dumped it. Some of the poorest of the poor lived in shacks on the dump. I recall Grandma Woody extending food credit to those who had nothing. I remember some paying their bill at the end of the month when they would receive a small pittance from somewhere, but I’m sure some just couldn’t, and I’m sure Grandma Woody worked something out with them.

During the business day, Grandma’s routine went something like this:

In the morning:

1..Here the bell on the store door ring

2..Stop cleaning, laundry, cooking, or making a bologna sandwich. Walk into the store.

3..Wait on a customer

4…Go back to her “housework.”

In the afternoon:

1..Here the bell

2..Get up from her living room chair in front of the television

3..Wait on a customer

4..Back to watching her afternoon “stories.”

5..Repeat

A room was built off her kitchen in the garage where her store stock and supplies were kept. Thursdays were freight days when that week’s boxes of replenishments arrived to be stacked in that room and then carried through the kitchen into the store. On many of those Thursdays, my Mom drove me to Grandma’s so I could help restock the shelves, and I loved it! Grandma named me head of the canned food division. I was marking everything in sight. Del Monte creamed corn 19 cents, Campbell’s tomato soup 12 cents, Hormel Spam 47 cents. I got the job done, and it was so much fun.

Ding-a-ling-ding-dong. Ding-a-ling-ding…the market door flung open; it was closing time, and the farmhands were coming into the market to grab their drinks from the cooler, say their goodbyes, and head home after a hard day’s work. Dad and I started cleaning up to get ready for the next day.

When we were finished sorting produce, sweeping, and restocking the coolers, Dad went into the house. I looked around my market, took a deep breath, and I could physically feel the love and enjoyment I had for what I was doing. Maybe, just, maybe, I was more of a Woody after all!

“Here’s to you, Grandma Woody, from the kid who remembers marking the cans of Chef Boyardee spaghetti and meatballs .29 cents with a grease pencil and was happily compensated with a creamsicle, an atomic fireball, and a flat meat sandwich.”

I never got the chance to meet my grandparents. This was an awesome story Steve, I loved hearing you narrate it!!

Sorry to hear that Ron. Thanks alot for taking the time to take a listen. Glad you enjoyed it and thank you for your consistant support of what I’m doing. I really appreciate it.

Great story. It’s fun to listen to reminisce

about the past. 🤗

James, thank you.

What a lovely remembrance of a wonderful lady! She was a treasure.

Dad and J!

Yup, she was a good one!